I’m Grace, and I’ve been part of the APE Lab since Spring 2024. I graduated with a degree in Psychology in May 2024, and will be starting a Couples and Family Therapy graduate program at Seattle

University this Fall. In the lab, I’ve had the chance to discuss and study topics like attachment, genetic conflict theory, friendship, and other topics related to the evolution of these theories.

My interest in how stress affects men and women differently led me to focus my independent project on

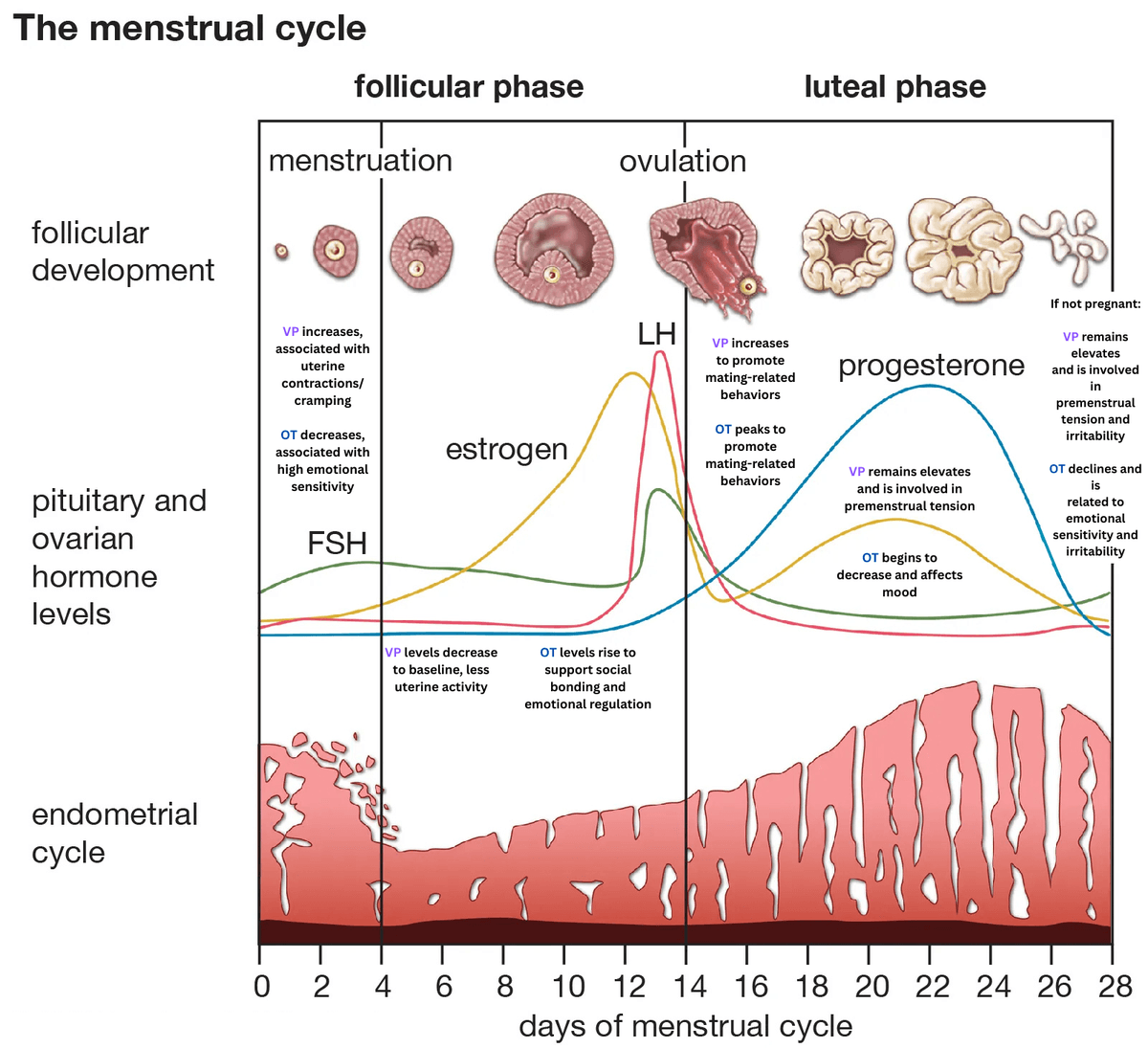

hormones and how they change over a woman’s life, specifically during menopause. We looked at four stages: premenopause, perimenopause, menopause (which surprisingly lasts only one day), and postmenopause. I wanted to see how these hormone shifts connect to mental health and stress during this big life change. I did this by reviewing existing research to figure out what we know and where the gaps are for future research. I focused on four hormones: estrogen, progesterone, vasopressin, and oxytocin, and how they affect the body’s stress response.

In my first project, I looked at estrogen and progesterone, two main reproductive hormones, and how they tie into stress. Estrogen affects cortisol, a key stress hormone. When estrogen levels go up and down and eventually drop during menopause, cortisol levels can become unpredictable. This might explain why many women feel more anxious during this time (Woods et al., 2009). Progesterone’s link to anxiety is more complex. Some studies show that low progesterone can make anxiety worse, while others find that too much progesterone can also cause problems. Either way, once women hit menopause and progesterone levels drop, anxiety often increases (Reynolds et al., 2019). Stress itself can throw these hormones off balance, as long-term stress in premenopausal women can lower estrogen and even lead to earlier menopause (Assad et al., 2017). Estrogen’s impact on stress can also change depending on what other hormones are doing (Stachenfeld, 2014).

In my second project, I looked at vasopressin (VP) and oxytocin (OT). They are “cousin” hormones, almost

identical except for one tiny difference in their amino acids, and both help with emotional regulation and stress. As estrogen drops, oxytocin also goes down. This can lead to mood swings and irritability (Dunietz et al., 2024). Women who go through surgical menopause often have even lower oxytocin, which can make their stress and anxiety worse. This is especially true for women with gynecologic cancer who have early, sudden menopause from surgery or radiation (Chang et al., 2019). Even though these women often have more severe symptoms, there are still no clear medical guidelines for treating menopause after cancer(DaSilva et al., 2025). Vasopressin helps control the release of stress hormones through the body’s stress system. Short-term activation is normal and helpful, but chronic activation can raise the risk of

anxiety and depression. During menopause, lower estrogen levels can make the brain more sensitive to vasopressin, which may trigger mood changes (Rigney et al., 2023).

Working on this project taught me a lot about hormones, women’s health, and myself as a researcher. It showed me how much we still need to learn, especially about how hormone changes affect stress and mental health in women. I also got better at reading and pulling together complex studies and turning them into something people can understand. Presenting my research at a national conference allowed me to share these ideas and learn from other researchers. It was exciting to see how my work connects to what others are doing and to think about how all of this can help women better understand what’s happening in their bodies.

References

Assad, S., Khan, H. H., Ghazanfar, H., Khan, Z. H., Mansoor, S., Rahman, M., Khan, G. H., Zafar, B., Tariq, U., & Assad, S. (2017). Role of sex hormone levels and psychological stress in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.1315

Chang, E. J., Davenport, E. R., Eggers, H. H., Shoupe, D., Roman, L. D., & Matsuo, K. (2019). Impact of radiation-induced menopause in young women with gynecological cancer.Fertility and Sterility, 111(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.071

Da Silva, A. L., Praça, M. S. L., Lamaita,R. M., Cândido, E. B., Paiva, L. H. S. D. C., Soares, J. M.,Marques, R. M., & Wender, M. C. O. (2025). Menopause in gynecologic cancer survivors: evidence for decision-making. Revista brasileira de ginecologia e obstetricia : revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecologia e Obstetricia, 47, e-FPS1. https://doi.org/10.61622/rbgo/2025FPS1

Dunietz, G. L., Tittle, L. J., Mumford, S. L., O’Brien, L. M., Baylin, A., Schisterman, E. F., Chervin, R. D., & Young, L. J. (2024, May 27). Oxytocin and Women’s Health in Midlife. The Journal of Endocrinology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11404667/

Reynolds, T.A., Makhanova, A., Marcinkowska, U. M., Jasienska, G., McNulty, J. K., Eckel,

L. A., Nikonova, L., &Maner, J. K. (2018). Progesterone and women’s anxiety across the menstrual cycle. Hormones and Behavior, 102,34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.04.008

Rigney, N., De Vries,G. J., & Petrulis, A. (2023). Modulation of social behavior by distinct vasopressin sources. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1127792

Stachenfeld, N. S. (2014).Hormonal changes during menopause and the impact on Fluid Regulation. Reproductive Sciences, 21(5),555–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719113518992

Woods, N. F., Mitchell, E. S., & Smith-DiJulio, K. (2009). Cortisol levels during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Menopause,16(4), 708–718. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318198d6b2